I like to emphasize that QE is a simple asset swap that happens after the primary asset issuance. That is, the government issues some amount of bonds when they run a deficit. And then the Central Bank implements QE by expanding their balance sheet by creating reserves and then swapping some quantity of those reserves for bonds. The private sector ends up holding more deposits and the Central Bank takes the bonds out of circulation. It is the logical equivalent of changing a savings account (the bond) into a checking account (the deposit). We don’t have more assets in aggregate even though we technically have more of what we call “money”. Another way of thinking about this is if the Treasury had just printed a deposit (instead of a bond) in the first place the Fed would have never had to do anything.

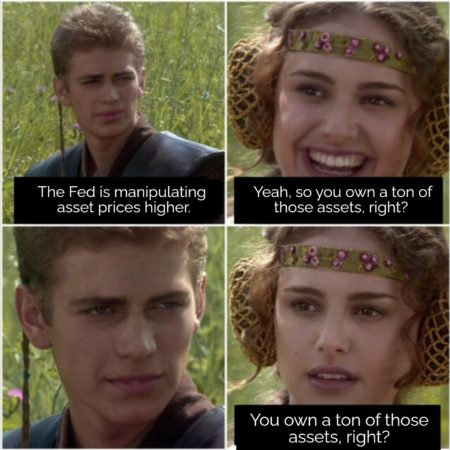

When viewed thru this lens it becomes clear that the real “asset printing” was done when the bonds were first created by the government’s deficit. The Central Bank’s operations just changed the composition of that prior balance sheet expansion. There are all sorts of knock-on effects from this policy (see the many channels of the monetary transmission mechanism here), but at the most basic level this is not “money printing” in the way most people assume. To me, this is the big lesson of the COVID stimulus response vs the Financial Crisis stimulus response – big government deficits create big inflation and QE is far less impactful.

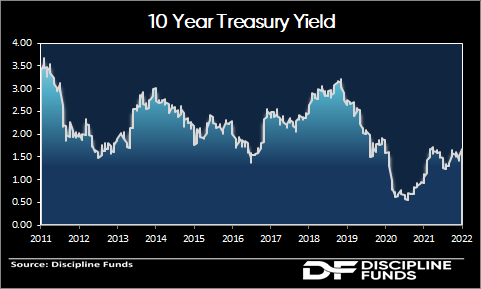

That’s a good segue into my actual topic of discussion here – Quantitative Tightening and demand for bonds. It seems like every time the Fed starts talking about unwinding QE people start  saying that this is the beginning of the end for the US bond market. If you remember way back in 2011 Bill Gross wrote a hyperbolic update about how the end of QE1 was going to be “D-Day” for the bond market. Yields were at 3.5% and he expected them to shoot higher because the demand for bonds would supposedly collapse without the Fed buying them. I wrote a public response in real-time saying he would be wrong. Counter-intuitively, the Fed stopped QE1 and yields cratered down to 1.5%. They’ve never recovered back to the levels that Gross said would be the low and long-term bonds are up 100% since then.

saying that this is the beginning of the end for the US bond market. If you remember way back in 2011 Bill Gross wrote a hyperbolic update about how the end of QE1 was going to be “D-Day” for the bond market. Yields were at 3.5% and he expected them to shoot higher because the demand for bonds would supposedly collapse without the Fed buying them. I wrote a public response in real-time saying he would be wrong. Counter-intuitively, the Fed stopped QE1 and yields cratered down to 1.5%. They’ve never recovered back to the levels that Gross said would be the low and long-term bonds are up 100% since then.

There’s a good lesson in all this mental gymnastics – THE GOVERNMENT DOESN’T NEED TO PAY YOU INTEREST. Now, this is very, very important. In theory, the US Government could fund all of its spending by issuing 0% overnight notes. They could run a deficit and just send brand new cash to the recipients of the excess spending. In this theoretical alternative reality the demand for government issued money relative to everything else would show up as inflation instead of some policy determined interest rate.

One of the ironclad laws of finance is that every financial asset that’s issued is held by someone all the time. So, dollars are a hot potato. You can trade that potato away to someone else, but you’re always just exchanging one potato for another potato or potato-like instrument. We cannot, in the aggregate, make the potatoes disappear. In a world where someone is always holding trillions of those 0% yielding notes you have to ask yourself whether you might prefer to hold a similarly safe asset that pays you 2%? That’s all a 30 year Treasury Bond is. In other words, any interest payment from government bonds is essentially a credit risk free subsidy to the person who doesn’t want to hold 0% yielding currency. In other, other words, if you were planning to hold your currency under your mattress for 30 years (which is what functionally happens to many dollars across time) then you’d be silly for not trading that instrument for a 30 year bond because you’d earn 2% interest every year.

There. Is. No. Alternative.

There. Is. No. Alternative.

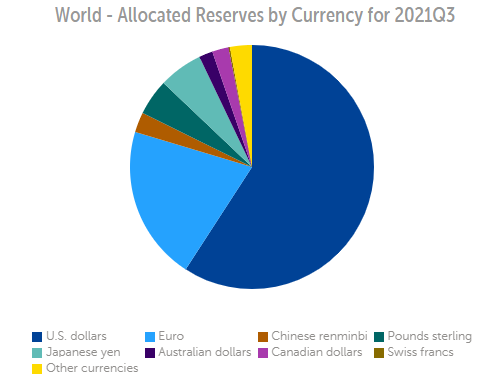

A related ironclad law of finance is relative value. If we all hold all of the financial assets outstanding then the price we’re willing to hold those assets at is a relative value measurement. When it comes to bonds and currency the USD simply does not have a competitor. And. It. Is. Not. Even. Close.

To put this in perspective you can look at total allocated global currency reserves.¹ The USD is 59% of the market. The Euro is a distant second at 20%. And the Yen is third at 6%. This will change over time. No doubt. I’ve said that it’s a matter of time before the USD loses its dominant reserve status and the USD’s relative weighting will likely shrink with time. But this will be a very, very long process mainly because there is no viable alternative at present. Europe doesn’t have a centralized government and fiscal authority. And China seems to be reverting back to a less trustworthy and more closed market system. It’s hard for me to see this situation changing any time soon given the relative value measurements at work here.² It’s kind of interesting to theorize about cryptocurrencies replacing fiat, but that space is so tiny and so new that it’s not even close to being a viable alternative at present.

Who will buy the bonds?

I’ve described interest rates as being similar to a dog on a leash. That is, the Fed walks the Treasury market around and decides how much the dog will move at any point. At the handle the Fed has absolute control of how much the leash moves. They set the overnight rate and the dog has no control over it. Yes, the dog can influence it. Sometimes it will run fast (think, high inflation) and sometimes it will run slow (think, low inflation). Sometimes it will stop to poop (think, recession). Heck, sometimes it will even go backwards (think, deflation). But if the Fed really wanted to it could bring that leash in all the way and grab that dog by the neck. This would be the functional equivalent of issuing currency at 0%, as I mentioned before.

For the dominant reserve currency in a world where positive interest payments are always a subsidy relative to 0% currency there is no point in asking “who will buy the bonds?”. It would be like asking “who will pick up the printed money?” in our scenario where the government finances spending by printing literal cash. No one would ever ask that question about Dollar currency, but they ask it about bonds for some weird reason. Except in this case the printed government liability pays interest and so is superior across maturity periods. In other words, someone will always pick up the printed money. This is especially true in a world of hot potatoes with relative value players where we’re debating the relative value of the dominant reserve currency. The point is, unless you believe hyperinflation is coming, there is no logical reason to question whether people will want to hold US government denominated liabilities. The more interesting question is, what is a sustainable rate of interest for the USD?

What is a sustainable rate of interest for the USD?

What does all of this mean for interest rates specifically? Well, our dog walker has made it pretty clear that they want the dog to slow down so they’re trying to rein it in some. The problem is, every time they try to slow our dog down they seem to overshoot or time the slowdown exactly wrong. This is why the Fed’s stimulus has become permanent. They want to rein the dog in, but every time they do the dog slows more than expected. Rinse, wash, repeat.

time they try to slow our dog down they seem to overshoot or time the slowdown exactly wrong. This is why the Fed’s stimulus has become permanent. They want to rein the dog in, but every time they do the dog slows more than expected. Rinse, wash, repeat.

So, how much room does the Fed have before the dog will freak out? Just looking at the current structure of the interest rate curve it looks like they have a relatively razor thin margin for error here. With 30 year yields at 2% the Fed could invert the yield curve with just a handful of hikes. And that’s the main problem here. The Fed has the dog on a tight leash, but the tight leash is evidence that the dog is more sensitive to potential changes which elicit a response.

Another way of thinking about this is asking yourself what would happen to inflation and the broader economy if the Fed shocked rates to 10% tomorrow morning? What would happen would be catastrophic for hyperinflationists. Mortgage rates, for instance, would skyrocket and the demand for housing would instantly collapse. All risk assets would reprice massively. You’d get an immediate deflationary shock that almost certainly causes a recession. This is obviously an extreme example, but the Fed is toying with a relative example of this where their margin for error appears much lower than some presume.

Conclusion

None of this means that interest rates can’t rise or that inflation won’t remain high. I’ve stated that I expect inflation to remain high well into 2022 and then moderate as the year goes on. But asking “who will buy the bonds” is like asking “who will pick up the printed money”? You will. I will. Because in a world of relative value where safe fiat currencies are scarce in a relative sense, it would be irrational not to want to gather up every last USD you can get your hands on because it’s the best currency in a world of bad currencies.

More importantly, the interesting question here is not whether people will buy the bonds, but whether the government can allow rates to rise much, if at all. As I’ve stated before, I think the Greenspan Conundrum is fully back in play here and that if the Fed starts raising rates aggressively they’ll find themselves backpedaling out of that position before long.

¹ – Source: IMF COFER.

² – To be honest, it’s shocking to me how many people talk about the demise of the USD when every single other fiat currency is much more likely to collapse. It’s like betting on Mike Trout to get demoted to the minor leagues when virtually every other player in the league is far more likely to get demoted. What?

NB – If you hold bonds and you also understand that bonds are long maturity instruments that are designed to be held to maturity while buffering your stock market risk then all of this is short-term noise that is inconsequential to you.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.