Here are some things I think I am thinking about:

1) Larry Kudlow as Chief Economic Advisor. Donald Trump has tapped Larry Kudlow of CNBC to be his Chief Economic Advisor. It’s an interesting and perfect pick if you ask me. Kudlow fills all the right boxes – he’s a yes man. He’s not a real economist. He’s a supply sider. And he’s a Reagan nostalgic who served as an associate director at the OMB during the Reagan administration.

Kudlow’s economic views are pretty benign in my view. He’s a free market guy, trickle downer, free trader and very wary of too much government intervention. I don’t agree with his views on trickle down economics or his persistent worry about government debt, but at a time when a global trade war is a rising risk he might actually talk some sense into Trump since he’s a big free trade advocate.

But it’s all more of the same if you ask me. Kudlow generally thinks that growth will solve all of our problems which is basically what Trump has always said. So you cut taxes (especially for the rich), the wealth trickles down over the economy and growth does the heavy lifting. It doesn’t actually work that way and trickle down economics has been shown to cause inequality and little else, but who needs facts in a world where everything that doesn’t support our priors can be brushed off as “fake news”?

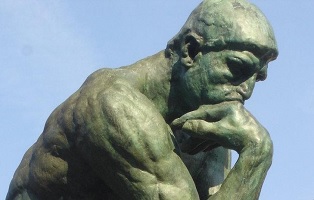

Anyhow, if you’re having trouble visualizing how Kudlow’s general theory of economics works I’ll let John Kenneth Galbraith clear that one up for you:

“Mr. David Stockman [also a trickle downer] has said that supply-side economics was merely a cover for the trickle-down approach to economic policy—what an older and less elegant generation called the horse-and-sparrow theory: If you feed the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows.”

2) Capex ain’t so great. I really liked this piece by Lawrence Hamtil on buybacks and Capex. We are constantly being barraged with stories about how buybacks are bad and companies need to invest more. This sounds nice and it’s obvious that companies need to invest to grow. But investment is also expensive, risky and difficult. A successful company can’t just pile every dollar back into some brilliant idea because brilliant ideas are hard to come by.

Interestingly, Lawrence shows us that companies that invest more don’t actually perform better. In fact, stocks with large buybacks seem to do much better than companies that invest more. This makes sense actually. Investment is expensive and risky. The companies with the most infrastructure intensive operations are constantly reinvesting in their operations and they tend to be low margin businesses. And while buybacks are often referred to as a form of “short-termism” they are actually best for long-term investors since they are designed to reward those who hold shares for long periods after the buybacks (because they increase relative ownership share to those who continue to hold the shares). Buybacks are just a low risk and tax efficient way of returning capital to shareholders. They are far from this evil form of spending that many purport them to be.

But the most interesting thing about all of this is how we keep reading articles from pundits screaming at Corporate America about how best to spend their money. You see, running a company is really damn hard. Most companies fail in the long run. And we know that stock pickers who try to pick the successful companies tend to perform poorly when compared to a broad index of companies.

It’s safe to assume that most of the people running companies know a lot more about that industry than the people who aren’t running those companies. And they have trouble running a successful business in most cases so it makes sense that someone outside of that business would have a difficult time assessing how successful that business will be.

So what on Earth makes any of us think that we know whether buybacks, dividends or more capital expenditure is the right way to spend corporate cash flows? The truth is that none of us knows better than the business operators (because they honestly don’t even know that well) and it’s about time we stop pretending that we know how to manage corporate cash flows better than the people who are involved in managing that business full-time.

3) The household vs government fallacy. Here’s a wonky paper from Roger Farmer at UCLA. He constructs a model for understanding why government finances are different from household finances.

But I wonder if Roger isn’t over-complicating things. After all, the main difference between a household and a government is that the government has a printing press and doesn’t have anyone to take it to bankruptcy court. So governments operating with a high degree of sovereignty don’t really face the risk of running out of money like a household. Instead, they face an inflation constraint. As I’ve written about in the past, these are similar, but different problems and it’s important to understand that they can have very different causes.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.