I am about 100% certain I think all of the following things I think I thought of:

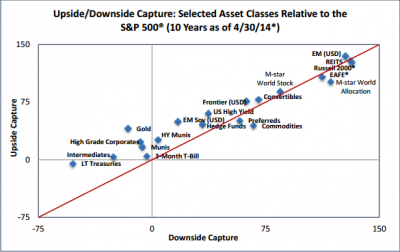

1) What is real diversification? I thought this bit of research by Richard Bernstein was pretty insightful. It shows the correlation between various asset classes and puts the concept of “diversification” in the right perspective.

Most of us think of “diversification” as different asset classes working together to create some non-correlation within a portfolio and hopefully a portfolio with lower overall variance and higher risk adjusted returns. But Richard shows us that most of the traditional asset classes are actually much more highly correlated than we might think. And perhaps the concept of “non-correlation” or negative correlation is less useful than some imply. In other words, most of the traditional asset classes do the same general thing over the long-term to varying degrees.

That means one thing – real diversification doesn’t just come from owning different asset classes, but also from putting those asset classes to work in different ways through different tactical approaches. The classic example is how some corporations hedge foreign exchange risk or commodity price risks to create certainty around their business model. Unfortunately, the same concept has been applied to more traditional portfolio management in what has often come as an expensive way to chase for the all too elusive alpha. But the excessive trading and irrational tactical approaches of some shouldn’t take away from the very real lesson at hand – hedging is not always and everywhere inappropriate. In fact, it’s often the most valuable form of diversification we can find if done inexpensively and appropriately.

2) Scott Sumner says Milton Friedman’s concept of “Monetarism” is mostly dead, but that young economists should strive to become the next Milton Friedman:

“I believe old monetarism is effectively dead. The monetarists (including Allan Meltzer) made enormous contributions to our understanding of monetary policy. But their model has reached a dead end. I implore bright young grad students with an interest in monetary economics to take a look at market monetarism.

…So if you are a bright young academic you have a golden opportunity to lead the movement—to become the next Milton Friedman. What’s stopping you?”

I can’t say that I understand the logic there. If traditional Monetarism, as Friedman constructed it, has been rendered largely void of value, then why should anyone strive to become the “next Milton Friedman”? Isn’t that unfair to a young aspiring economist to strive for such failure?

Jamie Galbraith has already done the heavy lifting here, explaining in vivid detail why Monetarism collapsed and why we should ignore many of its most important contributions, but it looks like memories are already fading fast. It would, in my opinion, be a real shame if too many young economists strive for what looks like imminent failure.

3) Is is the Fed’s tapering a “non-event”? It’s pretty interesting to see this post from the St Louis Fed on QE and tapering. They refer to the tapering as a “non-event”.

I’ve been pretty clear that I agree tapering isn’t tightening and that the economy can certainly still grow without QE. But this is also interesting to me because I wrote a paper several years back using Richard Koo’s description of QE as the “greatest monetary non-event”. Now, that wasn’t intended to imply that QE was unimportant or that it could do nothing. In fact, I’ve argued that QE has been tremendously important at times (such as QE1), but that its powers, effects and importance were vastly overstated. So it is interesting to note – if the St. Louis Fed sees tapering as a non-event then why should we assume that QE as a whole is not somewhat of a non-event as well? Or at a minimum, at least exaggerated by the mainstream media?

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.