Okay, I am a little OCD so bear with me here. Actually, if you plan on reading any of my work in the future you’ll have to bear with me for 30-50 more years since I assume this sort of griping will be a persistent trend given how badly I think the worlds of modern econ and finance have been mangled by politically motivated theorists (assuming my OCD doesn’t kill me first)….

Anyhow, I was reading some more Burton Malkiel thinking on the markets when I came across this gem from 3 years ago. In this piece trashing US government bonds, Malkiel does something very strange. He makes the argument that dividend paying stocks are a good substitute for bonds. Now, I’ve seen this argument a lot over the years and we have to be VERY clear about something:

DIVIDEND PAYING STOCKS ARE NOT A SAFE SUBSTITUTE FOR BONDS! EVER! EVER!

Did I write that big enough? Maybe not. Let’s try again:

DIVIDEND PAYING STOCKS ARE NOT A SAFE SUBSTITUTE FOR BONDS! EVER! EVER!

Okay, you get my point. Of course, saying it isn’t enough. There should be some empirical data to back up this assertion. First, a bear market in bonds is nothing like a bear market in stocks. When someone compares the two instruments it means there is a high likelihood that they don’t understand the capital structure very well and haven’t connected all the dots here. A fixed income instrument has several embedded safety components that make it entirely different from stocks:

- It’s higher in the liquidation chain.

- It pays a “fixed income” over the course of its life.

- If held to maturity fixed income pays you back at par.

- The duration on a fixed income instrument is generally shorter than that of common stock.

This explains why fixed income is inherently safer than common stock. We can see this in the performance data. Since 1928 the 10 year US Treasury note has been negative in just 14 calendar years. Those negative years averaged a -4.2% return. Stocks, on the other hand, have been negative in 24 of those calendar years and with an average decline of -13.6%. The worst calendar year decline in stocks was -43% while the worst calendar year decline in bonds was -11%. So it should be clear that a bear market in bonds is very different from a bear market in stocks.

But what about high dividend paying stocks? People often confuse dividends for making an equity instrument similar in some way to a fixed income instrument. This is completely wrong. An equity instrument that pays a dividend still lacks all of the aforementioned built-in safety components that differentiate fixed income from common stock. It just means the company pays a dividend stream (which isn’t actually fixed and can be revoked at any point as many people found out during the financial crisis).

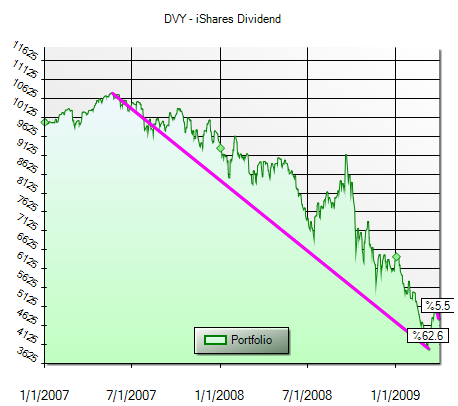

More importantly, dividend paying stocks can be atrocious performers at times. And it’s often because high dividend paying stocks are leveraged companies who borrow funds to finance dividends and operations. This was most obvious during the financial crisis. Take for instance, the iShares Dividend fund which cratered -62% during the financial crisis.

Going back to Malkiel though – I had to chuckle at this bit of “Random Walk” advice from 2011 when he recommend buying AT&T stock because it’s a high quality dividend paying stock:

“Another strategy would be to substitute a portfolio of blue-chip stocks with generous dividends for an equivalent high-quality U.S. bond portfolio. Many excellent U.S. common stocks have dividend yields that compare very favorably with the bonds issued by the same companies.

One example is AT&T. The dividends paid on the company’s stock result in yields close to 6%, almost double the yield on 10-year AT&T bonds. And AT&T has raised its dividend at a compound annual growth rate of 5% from 1985 to the present.”

Since then AT&T has generated a 36% total return. Not bad! Except for the fact that the high quality blue chip index of the S&P 500 has generated a 67% total return over the same period. In other words, Malkiel got trounced for engaging in the exact type of activity he mocked stock pickers for engaging in in this recent WealthFront blog post. The level of inconsistency and hypocrisy in some of this writing disturbs me, to say the least. One of the most influential thinkers in modern finance is just blatantly contradicting himself in these commentaries and yet people cite his work when it’s convenient to a certain perspective. That’s rubbish in my opinion.

Okay, I’ll lay off Malkiel now. But you should be starting to see a common thread in a lot of this work. There are disturbing inconsistencies and misunderstadings in the views and framework that a lot of this work is built on. And an entire industry has come to believe that this sort of thinking is a solid cornerstone for thought!

(pulls out hair)

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

John Daschbach

The debt vs. equity argument over generational time frames is largely dependent upon the tax structure and changes in same. Common stocks and similar equity have carried an incredible multigenerational tax advantage over debt, especially in recent decades. Aside from that, you have to evaluate the real return over time in the context of any agents tax situation. While many incorrectly argue the Fed has induced a chase for yield the reality is probably much more related to tax structure.

All but one of my friends and family who have total incomes above $500K/year report that ca. 1/2 is in equity grants and options. If your smart and have wage income in the moderate range ($100K – $300K) you accept more in equity which you can get better tax preferences on beyond 1 year.

Almost everyone who has a significant impact in the current US economy gets ca. at least 1/3 of their compensation in equity or other lower taxed future payment streams like health care.

There is no point in comparing assets over a reasonably long term without some evaluation of the tax implications. In the US, politicians are fundamentally traders in tax preferences, from lower capital gains to solar energy tax credits.

You can’t evaluate bonds vs. stocks without a model which includes taxes, inflation, and the government response in a time of crisis. We don’t have that model.

Bluidbouy

Hear hear!

Taking Stock

Bonds pay a fixed, never rising income. Careful stock selection can create a low-risk portfolio where your income rises every year. In a choice between fixed never rising income and an income that rises every year, it should not be a difficult decision.

quaking

Agreed.

If we define risk as short-term fluctuation in price, then bonds are safer than stocks. But if the risk is that you will have less future income, then bonds carry more risk than a diversified portfolio of dividend paying stocks.

Cullen Roche

Here’s how I think of it. Risk is the potential that you won’t meet your financial goals. As that pertains to a portfolio, the biggest risks are permanent loss and purchasing power loss. If you buy stocks you are overweighting purchasing power loss. If you overweight bonds/cash you are overweighting permanent loss. The key to asset allocation is balancing this understanding with your goals and financial needs and adjusting it appropriately over the course of the business cycle.

quaking

The risk of permanent loss in a diversified or index fund would appear to be very low.

I mean, if you view stock ownership as a stake in a real enterprise, you can pretty much safely exclude that as a calculation — if American businesses are worth zero then you have no safe haven.

Cullen Roche

Well, that depends. If you live in Greece or Italy or Spain or China and you’ve had a home bias in equities then the risk of permanent loss feels quite real to you.

Even owning a total world index could expose you to periods of substantial risk of permanent loss. Even a 60/40 was down 33% in 2008 from peak to trough. The risk of that loss is way too much for a lot of people to stand….So it depends. Telling an investor to “just hang on for the long-term” is cute in theory, but it really effs up your life when you actually go through it. Of course, lots and lots of people come back in hindsight and say “see, stocks for the long-run!” Without fail, these oversimplified academic narratives dominate the commentary…These narratives exist in large part to help people promote a product or theory so they can raise assets or win prizes. They don’t exist so you can actually manage your money in a way that actually relates to YOUR life.

Taking Stock

Owning a broad index of stocks is different than owning say a more concentrated well-screened list of extremely conservative dividend-growth stocks. This is where I (and others) have invested successfully for decades. If you own, for example, companies whose free cash flow is virtually guaranteed to rise because of their business model (you have to do your homework) , and thus their dividend which is based on FCF will rise as well, year after year, it is virtually impossible to not outperform. I’ve been doing this since the end of 1986 and have averaged 15.24% per year over that time. My single worst year was 2008 when my overall portfolio declined a relatively modest (my view) 13%. I’ve had four negative years and 23 positive ones over that time. My portfolio is largely pipelines and utilities where their income comes mostly from regulated operations or long-term contracts. Enbridge (ENB) is an example of the kinds of stocks this portfolio owns. My dividend will be going up at least another 10% later this year. Can’t get that in a bond. Take a look at http://www.enbridge.com. By the way, ENB’s single worst rolling 10-year return over that 27 years has been +137% (worst ever) and it’s average 10-year return has been +350%. One of many such companies. There are ways….

Taking Stock

Agree. How many people would agree to be employed for an income / salary for decades that never rises? That’s what they agree to when they buy a bond. In fact over the past few decades, they’ve actually seen their income shrink significantly and in real, inflation adjusted terms, they’ve been devastated, losing both income and capital.

panskeptic

Burton Malkiel got famous saying that all pertinent information is priced into a stock, so Graham, Buffett and Co. can’t make money on mispricings. And we know how that turned out.

Malkiel has been wrong more often than he’s right. If you think he’s embarrassing 2011-2014, check him out 2008-2009.

He’s nowhere near as entertaining as Marc Faber, who’s also consistently wrong. I can’t for the life of me figure out why anybody listens to Malkiel.

JUDS1234567

This is so true, I remember reading a comment about their being no Jack Bogles in countries like China, Germany, Russia, Spain, Italy, Japan, Korea, Most of Europe and Latin America. Is it a coincidence that the countries that came unscathed from the world wars espouse stocks?

(Canada, Australia, Nordic Countries)

quaking

I doubt the bourses in Span, Italy, France ever went to zero, either!

Most of my clients in 60-40 or even 80-20 mixes got through the crisis.

The ones who really freaked were those who held high yeild or Fannie Mae bonds and saw their prices crater. Not to mention the unfortunate few who held Lehman bonds the trading desk assured me were rock solid.

Cullen Roche

I think the issue is that most people don’t want to “go through” that kind of negative drawdown to begin with. When you go through a 30-40% drawdown in a 60/40 it takes 5-10 years on average just to break-even. Sometimes longer in real terms. Most people out there think of their portfolios as their life’s savings. And these sorts of disruptions in a portfolio can be extremely traumatic. Telling people “oh, just put your life on hold for 5 years, everything will come back” is just not a very reasonable thing to have to tell people. But that’s what every indexer basically says.

Worst part is, 60/40 has basically become the benchmark. You’ve got all these knuckleheads running back tests using the greatest bond bull in history on 40% of their portfolio assuming the same equity risk premium and saying “worked for the last 30 years, should work for the next 30 years”. This is among the most naive things I see these days. A 60/40 from 2014-2044 will look NOTHING like a 60/40 from 1984-2014. And anyone who is constructing a portfolio under that sort of rear view mirror “efficient market” thinking is in for a real treat in the coming 30 year cycle….You don’t need my level of macro understanding or to make complex forecasts to conclude that bonds are not going to generate 8% returns like they did in the last 30 years and the equity risk premium on stocks is almost certainly going to be much lower than it has been.

All of this “markets are efficient”, “buy the passive index”, “I don’t rely on forecasts” stuff is just bunk. It’s all thought up by people who don’t understand macro econ or macro finance and academics who haven’t done much work in the field actually implementing their ideas. Most of them just came up with some cute political theory, twisted it into finance theory, ran some data that confirmed their biases and then marketed the hell out of it….Unfortunately, a lot of it has actually caught on.