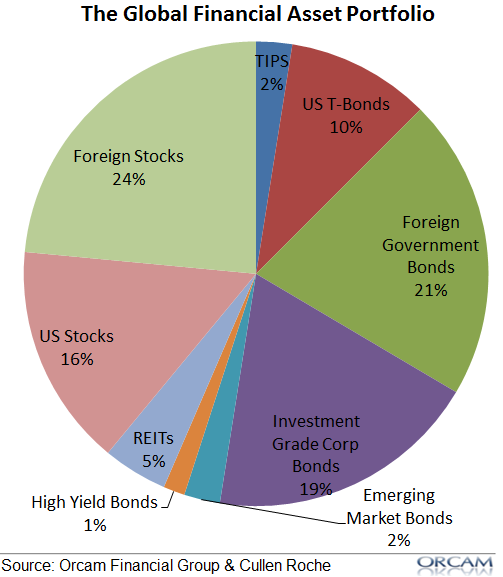

Last week I presented the Global Financial Asset Portfolio (GFAP). In case you missed it here’s a brief summary:

- The GFAP represents the current allocation of the world’s financial assets.

- The GFAP is the only pure “passive” index as this is the index that gives you “what the market gives you”.

- The GFAP is approximately a 55% bonds, 40% stocks, 5% REITs index at present.

- The GFAP has performed extremely well in the last 30 years on both a risk adjusted and nominal basis.

While I think this portfolio could be fine for many people I also believe this analysis has exposed several flaws in the traditional view of “forecast free” and “passive” investing. Instead, this analysis requires us all to take a much more nuanced perspective. It’s very likely that the people selling the idea of a purely “passive” or “forecast free” approach do not understand the underlying dynamics at work. Let me explain.

First, as I explained previously, the true global asset portfolio (as depicted in this paper), is impossible to replicate perfectly. So there is really no such thing as buying exactly what the “market gives you”. You have to alter the index using various subjective assumptions. In the case of my GFAP I removed commodities for instance because I wanted to remove non-financial assets based on the understanding that commodities don’t perform well in real terms over the long-term. Clearly, that’s been somewhat wrong over the last 15 years as some commodities have performed extremely well. But the point is that there’s a degree of subjectivity here that makes this a much more nuanced and active endeavor than we might think.

Second, the GFAP is an ex-post snapshot of what the financial asset world looks like today. Historically, the GFAP should change over time as the underlying balance of assets will inevitably change over time. So the GFAP has to be reactively dynamic to some degree. Therefore, the portfolio requires its own degree of reallocation just to remain consistent with the actual underlying allocation of outstanding financial assets.

Third, because the GFAP is an ex-post snapshot of the underlying financial assets it is inherently reactive. Therefore, it could be positioned in such a manner that it will not provide optimal future returns. For instance, today’s balance of financial assets reflects the falling interest rate environment of the last 30 years. So the GFAP reflects this balance. As a result, the portfolio is bond heavy relative to equities because it has become significantly less expensive to issue debt relative to equity over the last 30 years. As a result we’ve seen a huge decline in equity issuance relative to debt. So the GFAP has shifted from what was a stock heavy portfolio 30 years ago to a bond heavy portfolio today. But this is a reactive shift in the landscape. Any smart asset allocator would look at this environment and argue that there are some unsustainable trends in place here.*

For instance, the Aggregate Bond Index has generated 8%+ annualized returns since 1980. With overnight interest rates at 0% there is about a 0% chance that bonds will generate the same returns in the next 30 years as they have in the past 30 years. So this bond heavy portfolio has an overweight to fixed income thanks to the ex-post nature of this index. But there’s also a strong argument to be made that stocks are expensive in relative terms and likely to be more volatile going forward than they have been in the past. This means that anyone actively choosing to deviate from the GFAP bond heavy allocation is potentially exposing themselves to a high degree of equity market risk which creates a whole other risk for investors in a low interest rate environment.

More specifically, we should caution against the use of a pure market cap weighted index like the GFAP because it could expose investors to higher levels of risk than they believe they are taking. For instance, the equity piece is inherently procyclical and could be overweight stocks in certain parts of the world at their riskiest times. After all, market caps increase because portfolios have performed well in the past. Additionally, on the bond side, investors in certain types of bonds (such as international bonds, high yield bonds, etc) should be aware of the fact that many of these instruments act more like stocks than bonds during times of distress. This means you could be compounding the exposure to tail risk in the GFAP by allocating to these instruments with the assumption that they are true “fixed income” safe havens.

Lastly, we should note that there are many factors that play into an asset allocation decision outside of trying to replicate a “pure” index like the GFAP (there is a degree of indexing overkill in some discussions these days). Clearly, this allocation isn’t appropriate for all investors and you need to be very precise about understanding risk and how it relates to your personal decision before you can allocate your assets appropriately. So generalizations about the GFAP should be taken with a grain of salt as they do not apply to everyone.

All of this presents an interesting conundrum for asset allocators. Using an ex-post snapshot of the financial world is clearly not always an optimal approach for everyone. Most importantly, there’s an obvious contradiction in the idea that we should just accept “what the market gives us” since this implies that the forecasts of the asset issuing entities comprising the current underlying asset allocation, is optimal, and we should therefore just accept the return that their asset issuance generates.

A reliance on a “pure” indexing approach like the GFAP is not necessarily a bad idea for some people, but it has obvious flaws as well. Asset allocation requires a certain degree of active forecasting and “asset picking” based on how we think the future performance of specific asset classes will translate to our risk profile and financial goals. There’s a certain degree of forecasting and guesswork involved in any of this. A reliance on a pure ex-post approach is reactive and static relative to what must be a proactive and dynamic endeavor (asset allocation). Finding the perfect balance will be difficult for all of us to achieve. Hopefully this series helps you put things in the right perspective so you can come a little closer to optimizing your own approach.

* To highlight this point consider the fact that a 40/60 bond/stock portfolio has substantially outperformed a 60/40 bond/stock portfolio over the last 30 years on a risk adjusted basis and only slightly underperformed in nominal terms. In other words, buying the GFAP from 30 years ago when it told us to be stock heavy, was precisely backwards!

Related:

- Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Know About Money and Finance

- Debunking some Common Investment Myths

- We Are All “Active” Investors

- Most Index Funds are Macro Funds

- Putting the “Underperformance” of Active Managers in Perspective

- Of Course 80% of Active Managers Underperform the Market!

- There’s no Such Thing as “Forecast Free” Investing

- The Importance of Understanding Your Implicit and Explicit Forecasts

- The Importance of Understanding Your General Portfolio Framework

- The Contradiction of “Passive” Index Fund Investing

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Frederick

Great post Cullen. I’d love to hear what a BogleHead would think of this? They tend to be the ones who are most rabidly against the idea of forecasting anything. Your common sense approach appears to prove them wrong.

Cullen Roche

Funny you mention that. I actually saw some links come into the site from Morningstar’s BogleHeads forum a few weeks back. They were not having my “we’re all active investors” argument. But as I interacted with many of them I realized they weren’t really thinking this through entirely. They were essentially arguing that their “active” allocation styles were not really “active” at all. Instead, they argued they were grounded in Fama French factoring or other highly theoretical concepts that have come to be known as “passive” approaches even though they’re just arguments that have been cleverly constructed to give the appearance of rational market drivers. In other words, some people seem to take factor investing as being empirical rather than theoretical even though most of it is datamined and cherry picked to death.

The nice thing about using the GFAP approach is that you realize that deviating from it in any sense is an active decision that requires forecasting. The argument, in my view, is pretty cut and dry. If you don’t use the GFAP you’re trying to beat the GFAP which means you’re an “asset picker” trying to “beat the market” by making “forecasts”. It’s that simple. There’s no need to violently reject these concepts unless your marketing campaign and business model relies on differentiating yourself from “active” managers….

https://socialize.morningstar.com/NewSocialize/forums/p/340674/3565908.aspx#3565908

Frederick

Nice.

On a sidenote – from perusing the comments today I notice that there are almost no trolling comments. I think the change to Disqus is having a positive effect there!

Cullen Roche

I’ve noticed that also. Score one for Disqus so far…

pliu412

It seems that globe stock ratio 40/60 can be calculated by NIPA/Z1 https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=IuY. In this chart, stock ratio in 2014 Q1 is 40% consistent with GFAP data.

The detailed explanation is here

https://www.philosophicaleconomics.com/2013/12/the-single-greatest-predictor-of-future-stock-market-returns/.

It is interesting that Jesse claims this ratio is the best greatest predictor for stock market return in his article. It is a new way of thinking about stock valuation and may provide a theoretical foundation for this GFAP-based portfolio indexing method.

Cullen Roche

That’s extremely interesting in the context of this discussion. After all, if the future expected returns on stocks and bonds are low then what’s an investor to do????

Scott Weigle

What, if anything, do you think of the “permanent portfolio” (Harry Browne)? Not an index and not passive by your definition, but certainly an approach whose adherents claim to be superior over the long-term for those who don’t wish to prognosticate even a little bit.

Cullen Roche

A few general thoughts:

1) I don’t like holding 25% gold. In my opinion, gold has value only because people THINK it has value. It has no underlying output or cash flow value. So it’s a non-financial asset that has value largely because people THINK it has value. And if people stop believing that (for whatever reason) then its value will tank. Since I believe that there is a “faith put” under gold there is also a tail risk involved in owning it. Meaning that if the day ever comes where people stop believing that gold is “money” then its value will crash.

2) Also don’t love a 25% cash position in general. Especially not in an environment with 0% interest rates.

I don’t mind it for a slice of a portfolio, but I don’t think the underlying logic is very sound for an entire portfolio.

LVG

Great link. Meshes nicely with Cullen’s post. It makes me wonder though – if the key factor in future prices is the current allocation of assets and interest rates on cash and bonds are near zero then how can one position for the future? It seems that stocks have to be getting to a point where they’re becoming excessively risky given the low returns, but you can’t generate a sufficient return from bonds. So where to?

pliu412

According to Jesse’s theory based on the dynamic supply/demand, it implies the following:

An investor can get the future (assumed 10 years) expected return (which is low as you say), but he still needs to maintain his portfolio consistent with actual stock ratios in subsequent 10 years.

The future return, if based on any other stock ratios, could be estimated by considering them as the leveraged or de-leveraged stocks or bonds.

For example, 60/40 stock/bond ratio: leveraged 1.5x stocks and de-leveraged 1.5x bonds if actual stock/bond ratio is 40/60.

In general, leverage enlarges both return and risk compared to the market return/risk. But Sharpe and Sortino ratios are very likely to be lower as in your example.

pliu412

In this supply-and-demand dynamics, it seems that stock prices will get pushed up if supply of stocks cannot keep up with the continually increasing supply of cash and bonds. In Jesse’s article, it has an interesting explanation on this by using earningless bull markets.

Tyler Cruickshank

Thanks for this really great link. Fascinating yet full of what I would say feels like some very basic macro principles.

His dissection and “takedown” of Hussman’s expected returns model in his blog is also a tremendous read as well.

iitk64041

You write: “a 40/60 bond/stock portfolio has substantially outperformed a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio over the last 30 years .” The two portfolios are the same. Did you mean to say bond/stock for both the portfolios?