Executive Summary

Taxonomy is important in economics and finance as the precise meaning of words help us understand the complex financial world we live in. Unfortunately, much of the terminology we use in these fields has become muddled over time thanks in large part to political biases and opaque sales tactics used by its practitioners. Among the more confused terms is the “active” vs “passive” taxonomy which has resulted in substantial confusion among experts and amateur investors. In this piece I will explain the importance of this confusion and provide a clearer path forward that allows for more objective analysis of the financial world.

Introduction

The rise of low cost indexing is one of the most transformational trends in modern investing. It has completely changed the way we approach asset allocation. The growth and change in indexing has also transformed the traditional idea of what it means to be an index fund investor. After all, in today’s diverse world of index funds you are no longer tracking passive indices since you can now track almost anything in the world ranging from hedge funds, leveraged ETFs, to plain vanilla market cap weighted index funds. The rise of low cost diversified index funds has changed the meaning of an important debate in finance – the active vs passive debate. In this piece I will show that the rise of low cost indexing has changed the proper meaning of what it means to be a passive investor. In fact, I will show that, in a strict sense, there is no such thing as a passive investor.

The Importance of Accurate and Consistent Taxonomy

First, it’s important to be consistent and clear about the definition of active and passive investing. After all, passive investing is not just about reduced activity, low fees and tax efficiency as its name might infer. This is due to the fact that a stock picker who picks one stock and buys and holds it can be just as inactive as someone who buys one index and holds it. In fact, they’re likely to be more fee efficient than the indexer because there is no recurring cost to holding stock. So, this debate must be about more than activity, low fees and tax efficiency.

Further, new technologies such as ETFs have muddled the discussion here as there’s now an index of anything and everything. So, as Andrew Lo notes:

“Benchmark algorithms for high-performance computing blurred the line between passive and active.”¹

There are now systematic low fee index funds and ETFs ranging from market cap weighted indexes to index funds tracking short-term leveraged volatility indexes and even hedge funds. If we open the Prospectus of many ETFs we find that they’re calling themselves “passive” index funds whether they’re high fee hedge fund ETFs, leveraged volatility ETFs or plain vanilla index funds. Clearly, we shouldn’t call all of these indexes “passive” since they’re tracking strategies that have traditionally been referred to as “active” strategies.

The correct differentiating aspect between active and passive investing is that an active investor tries to “beat the market” on a risk adjusted basis while a passive investor tries to “take the market return”. Therefore, the investor who deviates from global cap weighting is explicitly stating that they can “beat” the risk adjusted returns of the aggregate global financial asset portfolio. In this sense, we are all active because we all deviate from global cap weighting. Of course, the industry does not adhere to this strict definition so it’s not very useful to call everyone an active investor. Instead, it is more useful to adhere to the aforementioned definition.

Active Investing – an asset allocation strategy with high relative frictions that attempts to “beat the market” return on a risk adjusted basis.

Passive Investing – an asset allocation strategy with low relative frictions that attempts to take the market return on a risk adjusted basis.

Thinking of the Markets in a Macro Sense

When we discuss the financial markets in this debate it’s important to look at the markets as an aggregate. And this means that there is one portfolio of all outstanding financial assets as detailed in this research piece. That is the global cap weighted portfolio of outstanding financial assets. Most of the “indexes” that people utilize in their portfolios are actively selected slices of this aggregate portfolio in much the same way that GE is one financial asset inside of the S&P 500. Likewise, the S&P 500 is one actively selected index of US stocks inside the global portfolio of all financial assets. The reason why the Global Financial Asset Portfolio is the one true “passive” portfolio is because it is, by definition, the only index which is not chosen with investor discretion. That is, its components exist purely based on the survivorship of the various assets that comprise it in a purely market dictated form. An index like the S&P 500, however, is an actively selected group of companies that represent a slice of outstanding global stocks. It is a deviation from global market cap weighting, by definition, thereby rendering it an actively selected index of US stocks.

The problem with this “active” vs “passive” distinction is that, when viewed through a macro lens, we all must be active asset pickers. There really is no such thing as passive investing and investors who don’t (at least unintentionally) try to beat the market. The reason why is because all investors deviate from global cap weighting and essentially pick micro components of the global financial asset portfolio. For instance, an indexer who owns the S&P 500 owns just 18% of the world’s financial assets inside of a much larger pie. They are essentially saying that they will deviate from global cap weighting because they believe they can perform better than the market cap weighted global portfolio of financial assets. This makes the indexer who owns slices of this global portfolio no different than the buy and hold stock picker who owns a slice of the S&P 500 (assuming tax and fee efficiency).

This simple point shows that the distinction between passive and active is really rather meaningless once we are all implementing tax and fee efficient portfolios. In essence, we all become asset pickers in this new indexing world. And some indexers MUST, by definition, be making smarter asset allocation decisions than others which leads to better performance. Although we might not be intentionally trying to “beat the market” when we deviate from global cap weighting there must be indexers who pick assets in a superior manner than others do.

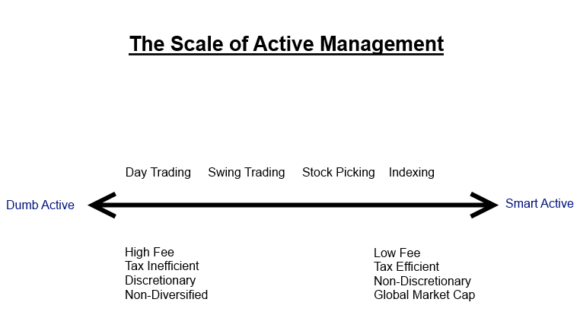

With that said, it can be more helpful to think of active management in terms of a scale as opposed to a “this or that” concept. So, if everyone is active because we all deviate from global cap weight then there are still smart ways to be active and stupid ways to be active. As a general guide, this scale of active management is helpful. In general, low fee, tax efficient and non-discretionary strategies are “smart active” while studies show that “dumb active” usually entails high fees, tax inefficiencies and discretionary intervention.

Operational Misunderstandings

One of the biggest misconceptions about indexing is that it is inherently inactive. But this doesn’t reflect the full circle of transactions that occur when one buys or sells an index fund. For instance, when an ETF is trading there is always a market price for the ETF (the price you see) as well as an intraday indicative value of the index the ETF tracks (the price the authorized participants see). If the market price were to deviate from the IIV then the market makers would either buy/sell the ETF or buy/sell the underlying securities. So, while there doesn’t appear to be much activity on the surface, the very act of buying an index could actually force some active management in the underlying securities markets.

As Rick Ferri, perhaps the most notable expert in the world when it comes to indexing says, “there’s no such thing as passive investing. It’s true. Passive investing in its purest form doesn’t exist. Only lesser degrees of active management exist.” Ferri goes on explaining that any index “must be continuously maintained by real people who face difficult issues when trying to track an index. The managers must make hundreds of active decisions each day concerning when to trade, what to trade, what to do with new cash, how to raise cash when needed, whether to use futures, swaps or other derivatives, etc. There’s nothing passive about managing an index fund.”

This means that indexing, by definition, creates the need for active management. There is no meaningful distinction because your purchase of an ETF could very likely result in some form of active management that you are, in some form or another, incurring the cost of (either the opportunity cost, spread cost, etc). In other words, indexing leads to active management. To make a distinction there is to look at only the surface level of the transaction. It’s like being in knee deep water and claiming to be “dry” because your upper body is not “wet”. This makes very little sense in the aggregate.

Your choice to index is an active decision that will necessarily lead to some underlying market making activity. In essence, your inactive choice in buying all 500 components of the S&P 500 leads someone else to be that much more active. The trade-off in exchange for your relatively inactive approach is that you incur some frictions in the form of opportunity cost, spread cost or other costs. These are marginal at the user level, but in the grand scheme of things can and do lead to big time profits for the underlying market makers (that share of the “active” market is certainly not going away). The point is, the transaction of indexing, full circle, is necessarily active even if, at the user level, it appears “passive”.

Inconsistencies in Macro Theory

In my search to establish a cohesive and seamless financial and monetary perspective of the world I keep running into one big problem with the idea of “passive indexing” – if the market is some all knowing all seeing thing then why don’t any index fund investors actually invest in the markets in a manner that is consistent with this belief? That is, at the aggregate level there is only one “market portfolio” made up of all outstanding global financial assets. Today, that portfolio is roughly a 45/55 stock/bond portfolio.

If the markets are so great at allocating assets then a truly passive investor would just take the market return and not deviate from this global cap weighted portfolio, but the vast majority of investors don’t actually do that. Almost invariably, they tilt towards a stock heavy portfolio and then say that “factor tilts” or “risk tolerance” are their reason for this “active” decision. But as Cliff Asness rightly says, you can’t deviate from global cap weighting and then pretend that you’re not making active investment decisions. If you deviate from 45/55 you are an active investor!

The idea of indexing originated, to a large degree, with the Chicago School of Economics. Economists at the school had already constructed a successful economic theory that argued that markets were more efficient than any form of discretionary intervention. This was an inherently anti-interventionist and anti-government view of the world (based on Milton Friedman’s Monetarism) that has since collapsed. But the general view was that discretionary intervention in a “market based” system is bad. Of course, this overlooked the fact that some degree of discretionary intervention is always necessary and in fact, in a creative destruction sense, is the very thing that drives innovation and economic growth. Thus, it is illogical and macro-inconsistent to argue that a “pure” market based system can exist. Some intervention isn’t just necessary, but is in fact good.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s some Chicago School economists extended this general economic thinking to the financial markets and argued that broad aggregates were better at digesting information efficiently than individuals. This was the foundational component of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. In essence, they argued that discretionary intervention in the markets was misguided. And while the general theory is correct, ie, free markets are generally good, some degree of intervention of some sort is good. We can argue about the relative need for activity or discretionary intervention, but we should not confuse this with thinking in absolute terms about these matters. And we should emphasize that any absolutism in this discussion will result in a theory that is not macro consistent.

The Great Strawmanning of “Active” Managers

A myth has developed that individual investors can beat all professional money managers because data has shown that index funds outperform stock picking mutual funds. Research has also shown that individuals tend to be very bad at managing their own assets (see here, here, here, here, and here). And we know this is true because individual investors tend to hold very high cash balances relative to all professional money managers (24% on average versus just 3.5% for the average equity mutual fund, for instance). Because stocks and bonds have historically outperformed T-Bills and cash it means that individual investors, in the aggregate, must underperform the more fully invested professionals. This is not necessarily due to the “skill” of the professional, but more likely due to manager career risk (managers feel obligated to invest cash) and behavioral biases of individuals (individuals tend to be their own worst investing enemy). So, the fact that stock picking mutual funds do worse than index funds does not mean the professionals do worse than individuals.

Unfortunately, there is much confusion surrounding this debate because of the studies that have been incorrectly performed on “active” managers. The whole concept differentiating “active vs passive” investing has been misconstrued based on a strawman argument against stock picking mutual funds. In reality, Vanguard has shown that the “active share” of a fund has no correlation to its performance. Instead, it is the high fees and high taxes incurred that tend to be the best predictor of the underperformance of a fund. Low fees predict better returns, not discretionary decisions, yet the media insists on differentiating this debate based on “active” decisions despite the fact that we are all active investors.

In addition, we know that many “passive” investors regularly underperform global aggregates as I showed in this study. And we know that the average investor tends to be very bad at managing their own portfolios. As indexing has grown to overtake stock picking we’ve all been forced to come to grips with the reality that we are all asset pickers inside of broad aggregates. Picking index funds is usually a more efficient form of asset picking than stock picking, but using index funds does not mean you are not being active at all. It just means you’re being a more efficient active investor than someone who pays high fees to trade stocks.

As I showed over the course of 2014 even the biggest advocates of “passive indexing” fail to eat their own cooking. Even John Bogle actively engages in asset picking. You have to be very careful listening to the various sales pitches on Wall Street these days. Paying someone 1.5% to help you “manage” a portfolio of Vanguard index funds (in which he will actively choose your allocation) is really no better than paying a stock picking mutual fund 1.5% to manage your assets. Yet it is regularly sold as something that’s “passive” and superior when all it really is is more high fee salesmanship. Sadly, the “passive” sales pitch, is now being used by high fee active managers to lure investors into thinking that they’re engaging in something superior.

The Active Decisions of the Passive Investor

Importantly, “passive” investors make lots of “active” decisions over the course of their lives. First, any asset allocator usually begins with cash or no assets at all. So any allocation to other assets is inherently active. Further, rebalancing, lump sum investing, contributions, distributions and “factor tilting” are all terms consistent with an active investment approach that are described as being passive. These are nothing more than marketing terms created by the “passive” investing community to give the appearance of something that involves no active decision making. And that doesn’t even touch on the fact that doing nothing is in fact an active decision in and of itself!

This doesn’t mean it’s unwise to focus on reducing taxes and fees as well as maximizing your compound returns. We know that reducing taxes and fees are the only ways to guarantee higher returns. But we shouldn’t assume that low fee is synonymous with intelligent asset allocation. After all, asset allocation will be the most important driver in your returns and while taxes and fees are important the active decisions involved in your asset allocation over time will play a substantially more important role in generating better returns. That is, your decision to be 60/40 as opposed to 70/30 will play a more important role in your returns than fees will (assuming you use low fee index funds).

Lastly, using low cost index funds does not make you any more passive than, say, a stock picker who buys and holds 500 stocks. In fact, it might actually cost more since you’re paying a recurring fee. And that doesn’t even touch on the fact that all index funds are actively chosen in the first place! There are management and structural decisions that go into the constituents of every index fund yet these funds are constantly put on display as being inactive when the reality is that they are not necessarily inactive, but merely low fee relative to many of their competitors.

The Temporal Problem in Modern Finance

It’s also important to remain realistic when considering this debate from a temporal perspective. That is, we have to be realistic about how we apply the textbook theory of the “long-term” to our financial realities. The “long-term” is a useful concept for general purposes and we should all be so lucky to have a truly long-term time horizon, but as JM Keynes said, “in the long run we are all dead”. While “passive indexing” is generally synonymous with “buy and hold” and long-term investing the reality is that we are often forced to think in shorter timeframes than modern finance would lead us to believe. Our financial lives don’t actually reflect anything close to the textbook “long-term”. Most of our financial lives are a series of short-terms inside of a long-term. We are constantly “timing” our financial decisions because our spending needs require us to be relatively short-term in many of our biggest spending decisions. Some degree of active asset allocation is not only wise in most cases, but totally consistent with maintaining a realistic risk profile. So the textbook models built on Modern Portfolio Theory don’t always translate well to our actual financial lives. This means that inactivity, while often desirable when maximizing tax and fee efficiencies, may not always be realistic.

Conclusion

The rise of index funds has turned us all into “asset pickers” instead of stock pickers yet the “passive” indexing community has tried to sell indexing as though it’s something totally different from stock picking. The reality is that we are all discretionary decision makers in our portfolios. Even the choice to do nothing is a discretionary decision. Therefore, all indexing approaches aren’t all that “passive”. They’re just different forms of active management that have been sold to investors using clever marketing terminology like “factor investing” and “smart beta” in order to differentiate the brands.

The rise of the low fee index fund is fantastic. Index funds are a vast improvement over many of the high fee stock picking funds that are out there. But we need to understand index funds for what they actually are and not what they’re marketed as. Get informed on this debate as it’s one of the most important debates of our times as indexing grows in popularity.

¹ – What is an Index? Lo, Andrew.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.