This page contains a brief review of some of the bigger myths in the world of economics. I hope you find it helpful.

1) Banks “multiply reserves and deposits”.

This myth derives from the concept of the money multiplier, which we all learn in any basic econ course. The theory says that banks that have $100 in reserves will then “multiply” this money 10X in some sort of causal nature that allows the bank to create more money than it otherwise could. This theory is one of the main reasons why so many famous economists predicted hyperinflation and the risk of high inflation following the Fed’s initiation of QE in 2008.

The problem with this theory is that it gets causality wrong. Banks don’t make lending decisions based on the quantity of reserves they hold. Banks lend to creditworthy customers who have demand for loans. If there’s no demand for loans it really doesn’t matter whether the bank wants to make loans. Not that it could “lend out” its reserves anyhow. Reserves are held in the interbank system and are only loaned to other banks. In other words, reserves don’t leave the banking system so the entire concept of the money multiplier and banks “lending reserves” is misleading.

It’s better to say that reserves and deposits can potentially contribute to capital which can help a bank bolster its balance sheet and leverage that into more loan potential. So while banks are required to obtain reserves there is no direct causal multiplier leading to more loans.

**Update** – The US government is now actively debunking this myth as well. Excellent.

See the following for more detail on the basics of banking:

- The Basics of Banking

- Loans create deposits and deposits fund loans

- The Myth of the Money Multiplier

- The Fed Debunks the Money Multiplier

- The Bank of England Debunks the Money Multiplier

2) Inflation is an Increase in the Money Supply

Some heterodox economic schools like to argue that inflation is an increase in the money supply. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but it can provide an incomplete understanding of inflation dynamics. Inflation, as defined by most macroeconomists, is a persistent increase in the price of a basket of goods and services. This basket, such as the CPI, is designed to reflect a median households annual consumption of goods and services. While imperfect, this measure has correlated very closely to broader macroeconomic indicators over time including commodity prices, GDP, bond yields, etc.

Using the money supply to define inflation can also lead to measurement problems. For example, in 2008 the Fed began QE, which swaps bonds for cash. This doesn’t change the quantity of net financial assets in the economy, but it does technically increase what we measure as “money”. This was the cause of many hyperinflation predictions in 2009/10 even though we now know QE is more akin to swapping a checking account with a savings account and therefore not very inflationary.

The important point regarding inflation is that it is generally more than a monetary phenomenon. We’ve seen this to be particularly true in the last 50 years where countries like Japan have printed huge amounts of money and inflation has remained low for various reasons including demographics, globalization, technology, politics, etc.

Further, the idea that inflation is an increase in the money supply is somewhat misleading since all money is credit in an endogenous monetary system. That is, the money supply pretty much always increases because people are borrowing money to produce and consume goods and services. There’s nothing inherently good or bad about an increase in credit. It really depends on how that credit is used and whether it results in the resources to support that new money. This depends on many factors and so oversimplifying all of this down to “more money is inflation” provides us with a very narrow understanding of inflation and its likely impact on living standards.

Related – Debunking the Chapwood Index and Shadow Stats

3) The Federal Reserve “prints money”.

The Fed really doesn’t “print money” in the way most people have come to think of it. Most of the money in our monetary system exists because banks created it through the loan creation process. The primary form of money the Fed creates is due to the process of notes, coin and reserve creation (which are distributed through the banking system in exchange for deposits/bonds and issued by the Fed and the Treasury). These forms of money, however, exist to facilitate the use of bank accounts. That is, they’re not issued directly to consumers, but rather are distributed through the banking system as bank customers need these forms of money usually by exchanging an existing asset for the new asset. For instance, when you take money out of the ATM you are swapping a bank deposit with a Federal Reserve Note. Similarly, when the Fed implements a policy like QE they are swapping reserves for T-bonds.

This myth is mostly due to misunderstandings of Federal Reserve policy and its relationship to Fiscal policy. In a technical sense, the Treasury prints money-like instruments when it runs a deficit. They expand private sector balance sheets by creating Treasury Bonds. They could, theoretically, fund their spending by printing physical cash. This would also be money printing. The Fed, however, is really just a big clearinghouse for banks. They create reserves, which are money for banks, and that money expansion doesn’t necessarily cause private sector financial asset quantities to increase. In other words, the Fed is mostly engaging in the process of changing the composition of the assets the Treasury creates (via policies like QE) while the Treasury is the actual asset printing entity in an aggregate sense.

In short, the Treasury prints financial assets when they run a deficit and the Fed is mostly engaging in changing the composition of the assets created by the Treasury as well as the banking system.

- What is Money?

- Where Does Money Come From?

- The Basics of Banking

- Where Does Cash Come From?

- Understanding Inside Money and Outside Money

- Understanding Moneyness

4) The US government is running out of money and must pay back the national debt.

There is a persistent belief that a nation with a printing press whose debt is denominated in the currency it can print, can become insolvent. There are many people who complain about the government “printing money” while also worrying about government solvency. It’s a strange contradiction when you think about it. After all, how could a nation with a printing press run out of money?

In reality the US government could theoretically print up as much money as it wanted. As I described in myth number 2, that’s not technically how the system is presently designed (because banks create most of the money), but that doesn’t mean the government is at risk of “running out of money”. More specifically, the US government is a contingent currency issuer and could always create the money needed to fund its own operations. Now, that doesn’t mean that this won’t contribute to high inflation or that there will always be demand to fund government spending, but solvency (not having access to money) is not the same thing as inflation (issuing too much money).

As for “paying back the national debt” – this appears to be a broader fallacy of composition. The liabilities of the economy are directly issued in accordance with the assets of the economy. That is, when the government borrows money they are creating both an asset and a liability. These liabilities are assets for the private sector. In order for the national debt to be “paid back” the government would have to run perpetual surpluses and shrink trillions in private sector assets.

The broader question is figuring out what level of government is necessary to have a healthy economy. It could be that a much smaller government makes sense and that would involve a smaller amount of outstanding government liabilities, but it’s very unrealistic to assume the government will “pay back” the national debt because that would necessarily involve winding down such a large portion of the government that it would be detrimental to private sector assets and broader economic health.

On a more technical accounting based note – balance sheets pretty much always expand in the long-run. Private sector liabilities AND assets will always expand in the long-run and so will net wealth. The expansion of liabilities (and debt) is not necessarily a bad thing because those liabilities help fund the assets that create net wealth. It’s certainly possible that the liabilities grow too fast and cause instability. This is also true of the government’s liabilities more generally, but the broader point is that the aggregate economy cannot “pay back” debts because the debts fund past, present and future assets.

** A related narrative here concerns “unfunded liabilities” such as Medicare and Social Security. These are future promises to pay that are not fully funded under future revenue expectations. These estimates are projected using long-term methodologies such as the 75 year outlook and the infinite horizon outlook. These projections are interesting, but require huge amounts of guesswork and are generally cited using the bigger of the figures from the infinite horizon outlook. The estimates from the 75 year and infinite horizon projections vary from $20T to $200T. More importantly these promises are by no means guaranteed. In fact, current law requires Social Security and Medicare to be fully funded so these projections wouldn’t even be legally permitted if they come to fruition. In other words, the government would have to reduce the budget or cut these liabilities to make them fundable.

See the following piece for more detail:

- The US Government is not Going Bankrupt

- Can a Sovereign Currency Issuer Default?

- Inflation is not Necessarily Another Form of Default

- Yes, the US government can afford the national debt and rising interest rates

- This commonly referenced USD purchasing power chart is useless

- The USD won’t always be the world’s reserve currency and it doesn’t matter

5) The national debt is a burden that will ruin our children’s futures.

The national debt is often portrayed as something that must be “paid back”. As if we are all born with a bill attached to our feet that we have to pay back to the government over the course of our lives. Of course, that’s not true at all. In fact, the national debt has been expanding since the dawn of the USA and has grown as the needs of US citizens have expanded over time. There’s really no such thing as “paying back” the national debt unless you think the government should be entirely eliminated. Otherwise, the government is generally growing to meet the growing needs of its domestic residents. The same basic point is true of the economy as a whole – balance sheets are generally expanding as we produce more assets (and liabilities) to help invest and consume over time. In fact, we should expect our aggregate balance sheet to expand over time, not contract.

This doesn’t mean the national debt is all good or that the government must always grow. The US government could very well spend money inefficiently or misallocate resources in a way that could lead to high inflation and result in lower living standards. There’s even reasonable arguments that the government is too big and could be reduced in size. But the government doesn’t necessarily reduce our children’s living standards by issuing debt. As mentioned above, the national debt is also a big chunk of the private sector’s savings so these assets are, in a way, a private sector benefit. The government’s spending policies could reduce future living standards in various ways, but we have to be careful about how broadly we paint with this brush. All government spending isn’t necessarily bad just like all private sector spending isn’t necessarily good. And at a macro level debt doesn’t get “paid back”. In a credit based monetary system debt is likely to expand and contract, but generally expand as the economy expands and balance sheets grow.

See the following pieces for more:

- The US Government is not “$16 Trillion in the hole”

- Is Social Security a Ponzi Scheme?

- Debt is Neither Good nor Bad by Necessity

6) QE is inflationary “money printing” and/or “debt monetization”.

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a form of monetary policy that involves the Fed expanding its balance sheet in order to alter the composition of the private sector’s balance sheet. This means the Fed is creating new money and buying private sector assets like MBS or T-bonds. When the Fed buys these assets it is technically “printing” new money, but it is also effectively “unprinting” the T-bond or MBS from the private sector.

When people call QE “money printing” they imply that there is magically more money and more assets in the private sector which will chase more goods which will lead to higher inflation. But since QE doesn’t change the private sector’s net worth (because it’s a swap of deposits for bonds) the operation is actually a lot more like changing a savings account into a checking account. This isn’t “money printing” in the sense that some imply.

See the following pieces for more detail:

7) Hyperinflation is caused by “money printing”.

Hyperinflation has been a big concern in recent years following QE and the sizable budget deficits in the USA. Many have tended to compare the USA to countries like Weimar or Zimbabwe to express their concerns. But if one actually studies historical hyperinflations you find that the causes of hyperinflations tend to be very specific events. Generally:

- Collapse in production.

- Rampant government corruption.

- Loss of a war.

- Regime change or regime collapse.

- Ceding of monetary sovereignty generally via a pegged currency or foreign denominated debt.

The hyperinflation in the USA never came because none of these things actually happened. Comparing the USA to Zimbabwe or Weimar was always an apples to oranges comparison.

See the following pieces for more detail:

8) Government spending drives up interest rates and bond vigilantes control interest rates.

Many economists believe that government spending “crowds out” private investment by forcing the private sector to compete for bonds in the mythical “loanable funds market”. This assumes that the government competes with the private sector for a fixed pool of funds and if the government competes for this money then they can drive up rates. This misunderstands modern banking and how banks create money. Banks do not create money from a fixed pool. They create money endogenously as I show here. Most economists do not understand banking very well so they use incorrect models of how money is actually created thereby resulting in this crowding out concept.

Further, the last 25 years blew huge holes in this concept. As the US government’s spending and deficits rose interest rates continue to drop like a rock. Clearly, government spending doesn’t necessarily drive up interest rates. And in fact, the Fed could theoretically control the entire yield curve of US government debt if it merely targeted a rate. All it would have to do is declare a rate and challenge any bond trader to compete at higher rates with the Fed’s bottomless barrel of reserves. Obviously, the Fed would win in setting the price because it is the reserve monopolist. So, the government could actually spend gazillions of dollars and set its rates at 0% permanently (which might cause high inflation, but you get the message).

The key point is in understanding that government bond markets aren’t really free markets. In the current monetary regime the US government chooses to pay interest on their liabilities. There is no reason why the government couldn’t fund its spending by issuing 0% interest bearing cash and there is no market mechanism that would force the government to raise interest rates on its debt. Importantly, this doesn’t mean the government has no funding constraint. High inflation can force the government to spend less or even run a surplus to control inflation. But this shouldn’t be confused with the mechanics of households and corporations and the way market forces can “bankrupt” them by forcing higher rates on their liabilities. This concept is different for a government in the sense that they can maintain 0% rates in perpetuity without having to worry about market forces sending rates higher.

See the following pieces for more detail:

9) The Fed was created by a secret cabal of bankers to wreck the US economy.

The Fed is a very confusing and sophisticated entity. The Fed catches a lot of flak because it doesn’t always execute monetary policy effectively. But monetary policy is not the reason why the Fed was created.

The Fed was created to help stabilize the US payments system and provide a clearinghouse where banks could meet to help settle interbank payments. This is the Fed’s primary purpose and it was modeled after the NY Clearinghouse. Private clearinghouses are inefficient in that they tend to fail during panics (because the private for-profit entities stop trusting other banks within the system). This became clear after the panic of 1907 which led to the Fed’s creation. The benefit of a public clearinghouse, as was clear in 2008, is that it doesn’t shutdown during panics. This is important because the banking panics of the 1800s and early 1900s would often exacerbate the pain in the real economy simply because the payment system shuts down.

2008 proved that the Fed could step in and act as a support mechanism to help keep mom and pop businesses from failing just because a bunch of stupid bankers refuse to settle their payments. So yes, the Fed exists to support banks.

None of this means the Fed is all good. I think there are logical arguments that policies like discretionary interest rate management and QE can have unintended consequences. And yes, the Fed often makes mistakes executing policies. But its design and structure is quite logical in a system where private banks dominate money creation.

See the following pieces for more detail:

https://pragcap.com/feds-dual-mandate-bull-sht

https://pragcap.com/who-owns-the-federal-reserve

https://pragcap.com/who-does-the-fed-serve

10) Fallacy of composition.

The biggest mistake in modern macroeconomics is probably the fallacy of composition. This is taking a concept that applies to an individual and applying it to everyone. For instance, if you save more then someone else had to dissave more. We aren’t all better off if we all save more. In order for us to save more, in the aggregate, we must spend (or invest) more. Or, we often tend to think of entire sectors as though they’re individuals. This leads people to think that corporations need to pay back their debts or that households in aggregate should pay back their debts when in fact debt is an asset and liability that is generally beneficial in the long-term.

As a whole, we tend not to think in a macro sense. We tend to think in a very narrow micro sense and often make mistakes by extrapolating personal experiences out to the aggregate economy. This is often a fallacious way to view the macroeconomy and leads to many misunderstandings. We need to think in a more macro way to understand the financial system.

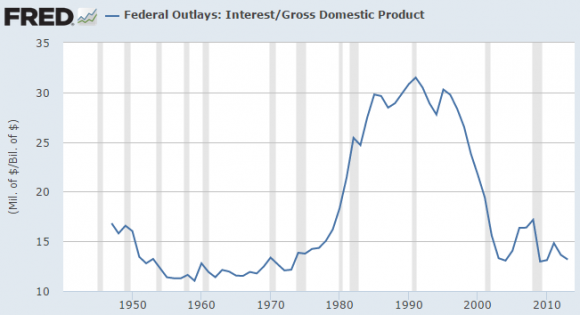

11) Interest Costs of the National Debt Will Lead to Uncontrollable Interest Burdens

This doesn’t make any sense. First, the national debt is the non-government’s asset. So its interest costs are a direct source of income for the non-government sector. It’s hypocritical for people to complain about low interest rates and high interest costs.

More importantly, The interest burden in the USA is actually declining as a % of GDP and is entirely controllable if the government desires. We pay about $250B in debt service every year. The Federal govt could actually reduce this substantially by reducing the maturity on their debt by issuing short-term debt instead of higher interest bearing long-term debt. They have complete control over their interest costs if they so desire.

There is no ironclad law that forces the US govt to raise interest rates. Just look at Japan where interest rates have been zero for two decades. A government that is sovereign in its currency, has no foreign denominated debt and a central bank that can issue its own currency does not have to worry about someone else telling them that they need to raise their interest costs. This interest cost is not controlled by “the market”. It is controlled by the monopoly supplier of reserves to the banking system (the central bank) and the Treasury which dictates the average outstanding maturity of the liabilities it issues. So this too is not a realistic concern.

See the following pieces for more detail:

- Who Determines Interest Rates?

- Yes, the US government can afford the national debt and manage rising rates.

12) Economics is a science.

Economics is often thought of as a science when the reality is that most of economics is just politics masquerading as operational facts. Keynesians will tell you that the government needs to spend more to generate better outcomes. Monetarists will tell you the Fed needs to execute a more independent and laissez-fairre policy approach through its various policies. Austrians will tell you that the government is bad and needs to be eliminated or reduced. All of these “schools” derive many of their understandings by constructing a political perspective and then adhering a world view around these biased perspectives. This leads to a huge amount of misconception which has led to the reason why I am even writing a post like this in the first place. Economics is indeed the dismal science. Dismal mainly because it’s dominated by policy analysts who are pitching political views as operational realities. It is, at best, a social science, but nothing resembling a hard science.

See the following piece for more detail:

- Economics is Mostly a Policy Debate Masquerading as a Science

- Economics is a Social Science, not a Natural Science

Nerdy High(er) Leverl Myth Additions:

13) The MV = Py Myth (aka, the equation of exchange)

I’m pulling this out of the forum because it’s a common question I see. Reader Oshe asked about the Equation of Exchange, otherwise known as MV=Py, where M is the quantity of money, P is the price level, Y is total output and V is velocity, or the number of times that a dollar is used to purchased goods and services. He asks how useful this equation and if its assumptions are valid. I don’t think so.

First off, we should be clear that the Equation of Exchange isn’t used by many economists these days. The old school Monetarists who relied on this sort of thinking are largely gone. This is the result of many erroneous assumptions in the theory that the empirical data doesn’t support.

That said, we can’t deny MV=Py. After all, this is just a tautology. You can’t debunk it. But you can poke serious holes in the assumptions that go into it. So, what are some of those erroneous assumptions?

a. MV = Py is only useful if V is constant. In this world V = Py/M. And if V isn’t constant then it can basically be fudged to mean whatever you want. So, if P is 1, Y is 1,000 and M is 10 then V has to equal 100. If you were an old school Monetarist then you would say that doubling M will double P because P=MV/y or P=((20*100)/1,000)=2. But what if P doesn’t double for some reason? Well, then you can just say V went down. In other words, the demand for money increased. The equation can mean whatever you want it to. That’s not very helpful.

b. The bigger problem in the Equation of Exchange is that it doesn’t define money accurately. “Money” in this model generally refers to the Monetary Base or Central Bank money. So, if you were applying an old school Monetarist sort of view then you’d have used this equation to conclude that QE would cause sky high inflation. In fact, we saw this sort of analysis all over the place in recent years. But the problem is that “money” is a really complex thing in a modern economy. It is not merely Monetary Base, cash, coins or even deposits. Money, as I’ve described, exists on a scale of moneyness and different things meet the properties of money in different instances. So, trying to peg “money” as Central Bank money is misleading at best and totally erroneous at worst.

In short, the Equation of Exchange is a very limited description of how the quantity of money actually impacts the economy and prices. And that’s primarily due to some broad theoretical assumptions that make it a lot less useful than many people think.

14) The Myth of the Natural Rate of Interest

The “natural rate of interest” is a theoretical concept in economics that describes the interest rate at which the economy operates at full employment with stable inflation. If we could calculate this figure then we could help devise policy that could steer the economy towards this “natural rate”. There are a few substantial problems with this concept:

a. There is no empirical evidence that this “natural rate” exists or that it can be sustained via policy.

b. The economy is not made up of one single interest rate so even if there is a natural rate we would have to discover millions of different natural rates in order to steer the economy towards an equilibrium point.

Of course, when one understands the operational reality of the monetary system it becomes clear that the Central Bank only has a very indirect control over interest rates. Therefore, even if this theoretical “natural rate” does exist then it’s unlikely that the Central Bank can do much to help us achieve that rate.

15) The Myth of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU)

NAIRU is a concept that describes the level of unemployment below which inflation rises. This is based on the idea that when there is little or no slack in the economy then inflation must necessarily rise. Economists theorize that they can calculate the figure at which that occurs although there is zero empirical evidence showing that this idea is valid or calculable.

A similar concept that often coincides with the use of NAIRU is the Phillips Curve. This concept became popular in the 1950’s when an inverse relationship between employment and inflation was shown in some data. This concept has not held up well over time, however. In fact, over the last 40 years the level of unemployment has consistently remained above estimates of NAIRU and yet inflation has continually declined. You would think that this would lead economists to dismiss this idea, but it is still very widely used.

16) American Living Standards are in Decline

The main argument against a broad increase in living standards is the fact that real median household incomes have stagnated for much of the last 30 years. This is undeniable and not a good sign for living standards. People often argue that the government has “debased” our currency and caused a direct reduction in living standards because our dollars don’t purchase as many goods and services as they once did. It’s common to see charts showing the decline in the US Dollar’s purchasing power since 1913. But these arguments, while correct in nominal terms, are wrong in real terms. For instance, Americans have achieved much higher living standards in the last 100 years DESPITE the fact that everything is more expensive.

As an example, just look at a simple act like washing clothes. A washing machine is obviously a huge increase in costs versus going to a river and scrubbing your clothing on a washboard. But the washboard cleaning could take you several hours a day and expends your effort as well while the washing machine, despite costing thousands of dollars more, is a wise investment because it affords you the ability to wash your clothes quickly while you are free to do other things. Technology has enhanced our lives in this manner in countless other ways despite the fact that the increased financing (money creation) in the process of these productive goods has increased the money supply. That is, our living standards have increased DESPITE the fact that the money supply has exploded because that money supply has produced goods and services that, in real terms, have made us significantly better off.

More importantly, the quantity of money we make isn’t necessarily a sign of being better or worse off. Instead, we should look at what those dollars buy and whether they afford us a better use of our time. In other words, do our current incomes give us more freedom to buy the things we want rather than the things we need. By this measure it is irrefutable that American living standards have improved dramatically even during a period when median incomes have stagnated.

A 2003 study from the BLS on American spending trends will help put this in some perspective. In the year 1900 80% of our expenditures went towards necessities (defined as housing, food and apparel by the BLS).³ Over the course of the next 115 years (I updated their study for the most recent data) we’ve seen that share of spending on necessities decline to just 48.9%. Therefore, even though incomes have stagnated for the median income earner that income affords them a higher living standard because it increasingly goes towards inessential spending.

The obvious response to this is that Americans now spend even more on things like healthcare and education, however, this isn’t accurate either. The median household spends just 10% of their income on healthcare and education. Therefore, we spend less today on apparel, food, shelter, healthcare and education than we spent on apparel, food and shelter in the 1970s. In other words, we spend so much less on the real necessities that now we can afford to spend even more on taking better care of our health and improving our intelligence. That’s a pretty definitive increase in living standards even for the person whose income has stagnated. So, despite stagnant incomes and a surging money supply Americans are significantly better off than they previously were.

There’s a lot more where that came from. You can read more myths here. I would also highly recommend my paper on the monetary system.

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.