How worrisome are soaring food prices? Wells Fargo says it depends and I think they’re right. This recent report succinctly summarized the fears over food prices and why the price increases are likely to cause far more trouble in the emerging markets than in the developed world. This is not to say that rising food prices won’t prove problematic in the developed world, however, the developed world is far less dependent on food costs as a percentage of total income than the emerging world. Therefore, I wouldn’t expect developed world central banks to react too negatively to rising food prices. Emerging market central banks, on the other hand, have a different battle on their hands and are now grappling to control what look like overheating economic conditions. (via Wells Fargo):

“Prices of grains, which are internationally traded commodities, have been rising sharply lately. As shown on the front page, corn prices are now within spitting distance of their 2008 highs. Wheat prices are further off of their previous peaks, but they too have moved up markedly in recent months. A combination of strong economic growth in some large developing countries, which has significantly increased the demand for foodstuffs, and poor harvests in some important food-producing nations, such as Australia, Russia and the Ukraine, seem to be behind the recent increase in food prices.

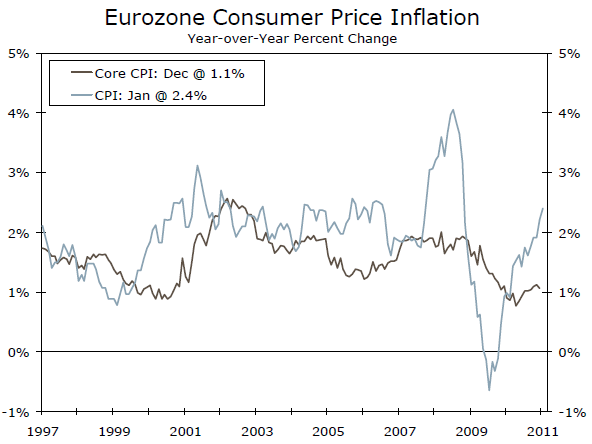

Do recent increases in food prices have implications for overall inflation rates and, in turn, central bank policy rates? The answer seems to be “it depends.” In our view, the increase in food prices has more inflationary pressures for developing economies than for advanced economies. Take the Eurozone, for example. Food accounts for only 15 percent of the consumer price index (CPI) in the Eurozone. Although the overall rate of CPI inflation has risen to 2.4 percent, which is above the European Central Bank’s (ECB) implicit target rate of around two percent, the core rate of inflation, which excludes food as well as energy prices, remains benign (top chart).”

“Our sense is that the ECB will hold fire as long as the core rate of inflation does not start to trend higher. In order for core prices to accelerate, workers would need to demand higher wages to compensate them for the recent rise in food prices. With the Eurozone unemployment rate at 10 percent, which is a 13-year high, workers probably don’t have much bargaining power at present. With overall labor costs in the Eurozone up only 0.8 percent over the past 12 months, it is difficult to envision a significant increase in wage inflation anytime soon.

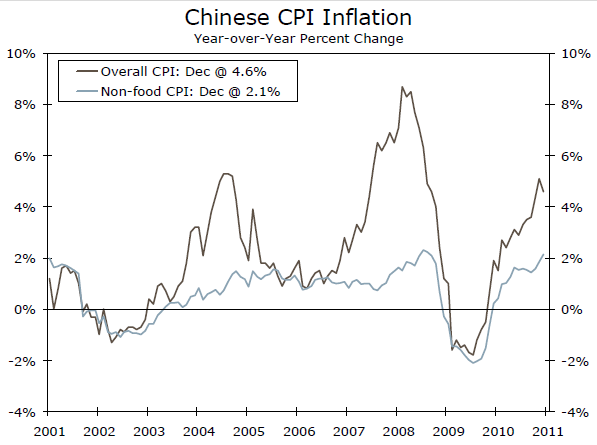

In contrast, we believe that the rise in food prices has more inflationary implications for developing countries, because food accounts for a higher proportion of the consumption basket in those countries. For example, food accounts for one-third of the CPI in China. Moreover, strong economic growth in many developing countries over the past year or so gives workers in some of those economies more bargaining power. Data on Chinese wages are not very current, but wage growth in China started to edge up in the second half of last year. The large wage concessions that workers were able to wrestle last year from Japanese auto manufacturers operating in China is consistent with the uptick in wage growth that is evident in the “hard” data. The run-up in food prices has lifted the overall rate of Chinese CPI inflation to five percent (middle chart).”

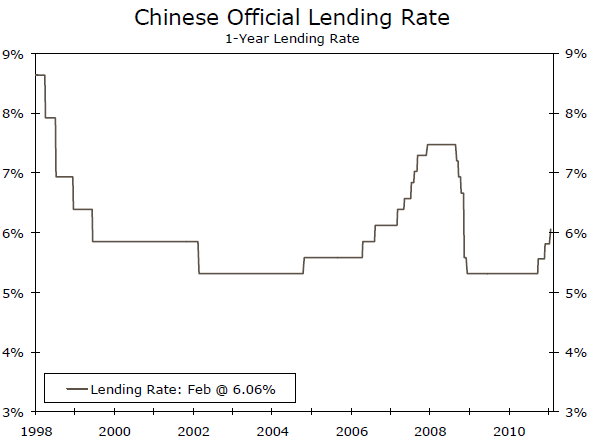

“More disturbingly, however, non-food price inflation has trended up to its highest rate since 2008 (middle chart). In response, the Chinese central bank has been tightening policy. Since October, the central bank has hiked its benchmark lending rate by 75 bps (bottom chart).”

“It has also raised the required reserve ratio by 200 bps since November in an attempt to drain some of the liquidity out of the banking system. Although Chinese authorities tend to change economic policies in a gradual fashion, the risk is growing that rising inflationary pressures will lead the central bank to tighten aggressively. This risk also applies to other important developing economies such as India. In our view, rising food prices represent a significant downside risk to economic growth in the developing world.”

Source: Wells Fargo

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.

Comments are closed.